Photo by twenty20photos

In a recent podcast episode of the Joe Rogan Experience, Rogan’s guest was Australian media personality Josh Szeps. The two began discussing the Pfizer vaccine and Rogan elaborated on a belief he had that the vaccine is potentially dangerous to boys and young men.

Specifically, he voiced concern that the vaccine was producing a concerning rate of myocarditis, an inflammation in the tissues of the heart. He presumably was referring to an article in The Guardian making such claims based on a study that used data from Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS). The VAERS has come under considerable scientific scrutiny given the nature of its self-report that leads to bias in the data gathered.

Later, the British Journal of Medicine would rebuke for reporting on unreliable data. But this did not appear to have swayed Rogan’s position.

This is not a surprise to anyone who has been paying attention to Rogan’s journey through the pandemic. Early in the pandemic, Rogan had a wider curiosity and had creditable guests on his show. In episode 1439, he had Dr. Michael Osterholm, one of the world’s foremost experts in infectious diseases, on his show. The pandemic was just gearing up and we all had more questions than answers. He laid out a now eerie prediction of what was to come. It was a fascinating conversation that clarified many things for me in the early days of the pandemic.

At that time people were disinfecting their groceries and Dr. Osterholm quietly but persistently told Rogan that this virus spreads through the air, not on surfaces. Personally, I found this conversation very informative of the true tragedy that had befallen the world.

Fast forward to 2022 and over 300 podcasts later, Rogan has since divorced himself from most of the creditable science on the topic. And, as a common psychological process, he started developing a greater bias toward disconfirming feedback.

So in this most recent conversation about vaccines and myocarditis, Szeps openly challenged Rogan’s assertion stating that boys and young men have a higher risk of myocarditis after contracting COVID-19 than with the vaccine.

Rogan immediately rejected the claim but appeared open to being presented with the information during the conversation.

Rogan read out loud many of the research findings reported in the New Scientist magazine that, in fact, disconfirmed his belief.

How did Rogan take the idea that his belief is, in fact, wrong?

Did he say, “oh wow, the research on this has shown me that my once held belief about the dangers of vaccines is, in fact, not substantiated by the data.”

Of course not.

He immediately rejected the information. Later, Rogan would state that Szeps made him “look dumb”.

No, he was wrong. And we’ve all been there. Maybe not with vaccination safety but perhaps with another misinformed belief or overgeneralized worldview.

Worst yet, if Rogan walks away from this interaction with the feeling that he was made to look dumb, then he is missing the point of the importance of being wrong — particularly when you are a social media influencer.

Let’s dive into how we can improve how to be wrong.

The Aversiveness of Being Wrong

Being wrong is a difficult place to be in. You would be hard-pressed to find a person who enjoys the feeling of getting something wrong, having the wrong idea, or being massively misinformed.

For most of us, being wrong can conjure up all manner of negative thoughts and emotions. It also may provoke memories of ridicule for being wrong.

But being wrong doesn’t have to be a bad thing. In fact, being wrong is an important experience and can sometimes help shape our thinking better than getting things right.

So if being wrong isn’t all that bad, why do we avoid it so much? Why do we struggle to let go of a belief despite clear evidence to the contrary? Why do we stubbornly pursue an ideology that proves itself to be flawed?

Why is it that when we are wrong, we may struggle, just as Rogan did, to admit it?

There are psychological and cultural reasons for this.

Believing is Seeing

Being wrong is a state that our brains almost automatically avoid. This makes a great deal of sense from an evolutionary perspective. Mass confusion about that state of reality would make humans more vulnerable to the dangers lurking on the edges of our herd.

So being wrong is difficult for our unconscious. I’m not talking about the Freudian unconscious, although that is an interesting thought experiment.

I’m talking about the tendency for our unconscious mind to construct justifications for our beliefs and actions automatically. I’m talking about the tendency of our minds to construct coherent narratives from fragments of the chaos of life.

The reason for this is what psychologists like to call coherence. Our minds like to make sure things make sense and that both the actions of ourselves and the events in the world are comprehensible.

In fact, you could say, that when it comes to the brain, believing is seeing — not seeing is believing.

Our brains do not demand that we get all the facts of a situation to produce coherence. Instead, our brains will stitch together coherent stories of why things are the way they are no matter the amount of information.

Psychologist Daniel Kahneman illuminates this point in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow stating, “Paradoxically, it is easier to construct a coherent story when you know little when there are fewer pieces to fit into the puzzle. Our comforting convictions that the world makes sense rests on a secure foundation: our almost unlimited ability to ignore our ignorance.”

But sometimes in our lives, we encounter contexts that show that what we believed was wrong, that we are ignorant to a given reality, or how we see the world is limited.

Let’s take Rogan, for example. At the exact moment that he is getting disconfirming information about his belief — there is a threat activated.

Rogan’s brain is not unique. It wants the world to make sense and it doesn’t like the tension created by holding two contradictory ideas, attitudes, beliefs, or opinions. In the 1950’s, social psychologist Leon Festinger would come to describe, with scientific clarity, this state as cognitive dissonance.

Cognitive Dissonance is an Asshole

Cognitive dissonance is a state of discontent and we unconsciously resolve this tension in an interesting way.

The beauty of Festinger’s research is it revealed an important truth surrounding human behavior. It revealed that when faced with a context that produces dissonance we do not necessarily resolve this tension by seeking out greater clarity of information. Instead, we can engage in a type of psychological contortion to justify our original beliefs — to keep things consistent.

In fact, you could say, that when it comes to the brain, believing is seeing — not seeing is believing.

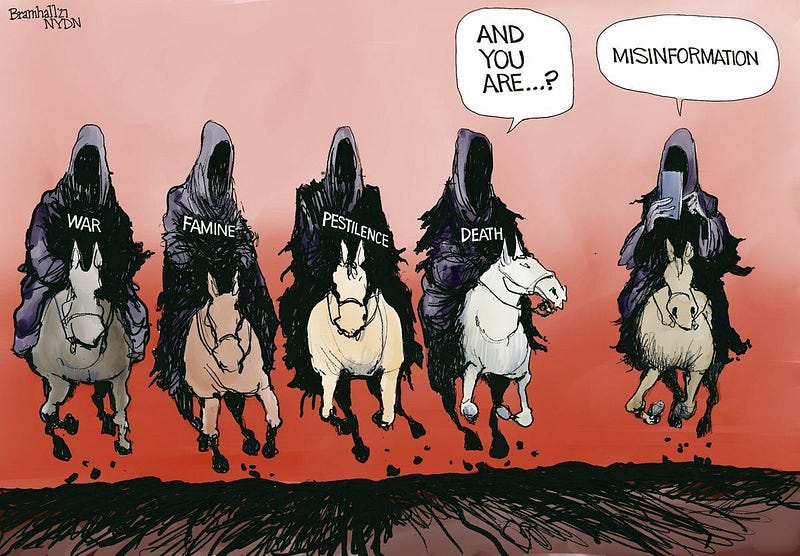

And one of the most interesting findings from research on cognitive distortion is that people’s beliefs can actually be strengthened, not weakened by disconfirming information. You see, when faced with disconfirming information we may automatically look for ways to criticize, distort, or dismiss it outright.

This is what Rogan did and it’s called the confirmation bias.

So our human psychology makes being wrong challenging, but that’s not the complete picture. Our culture, too, bears some responsibility for this as well.

You were Taught to be Right

We are socialized to be right — to find and report the right answer, to get things right, to understand people immediately, to make decisions that lead to success.

The emphasis on being right creates immobility in our society and quite frankly slows down our capacity to appropriately address the needs of our communities. You see this in many forms of government presently — where legislators act more like family fighting over Facebook than policymakers tasked with solving complex problems.

Additionally, we have placed images of infallibility at the forefront of our media. From Instagram filters to well-drafted speeches, we demand everyone to say the right things, to know the right subjects, have the right words, have the right image, and do the right things. Without exception.

Paradoxically, this actually fuels the psychological mechanisms of confirmation bias, prejudice, and self-justification. It also invigorates those who are only looking to instigate and troll for attention.

We can change this with a few considerations:

1. Hold Your Ideas Lightly

I would hope that we could encourage our culture to emphasize curiosity instead of knowing, emphasize repair over rupture, emphasize doubt over certainty, and emphasize humility over pride.

In his book Think Again, organizational psychologist Adam Grant notes that one of the reasons why we may find being wrong so unbearable is that we have a tendency to conflate our beliefs, ideas, and ideologies with our identity.

Grant states, “This can become a problem when it prevents us from changing our minds as the world changes and knowledge evolves. Our opinions can become so sacred that we grow hostile to the mere thought of being wrong, and the totalitarian ego leaps in to silence counterarguments, squash contrary evidence, and close the door on learning.”

Our culture has promoted the fusion of ideas and worldviews toward identities. Don’t get me wrong, some things lend themselves well to identities but we have seen a creeping growth here. Case in point, epidemiological science (or denial thereof) has become an intractable group difference in our mainstream culture.

Human belief systems, unfortunately, tend to become calcified unless we skillful work to keep our minds open. Once we firmly root ourselves in some kind of ideology, we become vulnerable to the changing contexts. We need to resist crystalizing ideas into identities.

This is particularly true during a global pandemic where both the knowledge of the virus and the virus itself are constantly changing.

2. Practice Humility

The world is not fully knowable and yet we act as if it is. As a result, we have to resist the temptation to foreclose our opinions about the world. We have to leave a space where new ideas and facts can have some influence.

The easiest way to do this is to practice humility — to realize that no one has everything figured out. We are all trying the understand this crazy thing called life.

We could encourage a culture that emphasizes growing instead of knowing, emphasizes repair over rupture, emphasizes doubt over certainty, and emphasizes humility over pride

Humility, one would hope, is the natural consequence of a good education. We become increasingly aware of how little we actually know!

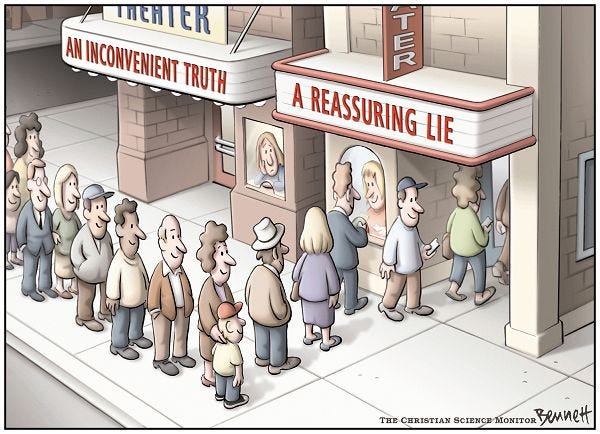

3. Education is Slow, Information is Fast

In the information age, there seems to be some confusion about the difference between knowledge and education. With so much information at our fingertips, there is a temptation to think we may know everything. Or perhaps we see something that confirms our belief and immediately believes it to be true.

But education is not the accumulation of facts. Education is a way of thinking — to have the awareness of our own thinking process, how we gather information, and how to systematically analyze the information presented.

An expert is not simply someone who holds all the knowledge of a particular domain (an impossibility in the modern era) — but a person who knows the appropriate questions and limitations of knowledge. As Albert Einstein said in 1921, “Education is not the learning of facts but the training of minds to think.”

This is one of the fundamental problems with social media celebrities like Rogan. They have influence because they have the capacity to spread information. And influence, rather than expertise, can be more influential in our information age. Good, creditable information may come slowly while misinformation can spread quickly. This can be exacerbated by folks spreading incorrect information.

We need to prioritize our education, not just getting facts.

4. Building a Relationship to Being Wrong

Being wrong is inevitable. So let’s focus on what kind of relationship we are going to have with it.

Our world is moving at such a rapid pace that we are not going to stay fully informed about things. We’re going to have ideas that are old and antiquated. We’re going to be ignorant of something important that we need to learn. We are going to fall for misinformation traps on occasion.

We need to be okay with being shown we are wrong — to be humbled by a truth that evaded our confirmation bias. And we need a culture that encourages people to own being wrong. We need a culture where being wrong is not bad but part of education. There is an art to being wrong and unfortunately few in public life have demonstrated such skills. ∎