Finding a sustainable way to stay engaged when the path ahead is difficult

The year 2020 has had a pronounced tie to suffering: fires consuming Australia, a global pandemic, global economic hardships, political unrest, and a crescendo of awareness surrounding racial injustice.

In the space of so much suffering and uncertainty, we can lose the motivation to stay engaged in the real work of making the world a better place. How do we hold so much pain without becoming overwhelmed or burning out?

We have to find some semblance of hope to move forward individually, as a society, and as a global community. But how?

The truth is I’ve never been a big fan of the concept of hope. I know that sounds particularly troublesome since I’m a psychologist, therapist, and counselor educator. As I will clarify here, it is not that I do not think that hope is unimportant. Instead, I believe that hope is unhelpful when it is framed outside the space of real suffering. In particular, I see many conceptions of hope to be troublesome when applied to problems that are multi-lateral and systemic. When tackling concerns such as racial justice, we must be very clear on how to constitute and sustain a sense of hope.

Before we can build an intentional space of hope, we must identify how hope, if construed problematically, may not serve such promising prospects.

Some Problems with Hope:

Part of my uneasiness about hope is how it is often construed. Hope frequently is described as some fairy dust that is sprinkled over the smolder of suffering to make us feel better. But I don’t think hope is a type of salve that we apply to help us feel better about the present circumstances. The problems of the world are too grand for something like that to work.

Hope, when superficially constructed, can offer absolutely no support in any meaningful endeavor. It is blown over easily by the prevailing winds of systemic homeostasis.

This is all to say that I am heedful to turn to hope in a cavalier fashion. Instead, hope has to be purposefully manifested deeply to help guide us through the storms of life.

The following are ways hope can be problematic, particularly when attempting cultural transformation and racial justice.

When Hope is Preoccupied with Short-Term Outcomes

Working toward desired outcomes is vital for everyone. When we set our minds to something, work hard, and achieve a positive result, there is a sense of accomplishment. But what if the things that we need to accomplish are large-scale, complex, multi-generational change?

When hope is conjured solely for short-term future attainment and achievement, then we see people engage in meaningful behavior only to the degree to which they believe near-immediate change is possible. The danger of this kind of hope is it readily stifles people’s efforts right out of the gate. If a tangible, immediate outcome is not known, then why engage? Secondly, if we engage in a meaningful movement and our efforts do not offer any explicit impact — why continue?

Now, this is not to say that orienting ourselves with goals and tangible outcomes is not a desirable capacity. It is. And we should have goals and desired outcomes in mind when we are engaging in personal, social, and ecological change. However, being solely preoccupied with particular short-term outcomes becomes a liability when we are trying to enact large-scale, complex change at the level of cultural change, justice reform, or ecological restoration.

The limits of this type of hope are easy to demonstrate. For example, we have one-session corporate diversity training programs that focus on presenting information to participants. Sure, in the session there might be some clever interventions and provocative information. But we know from the psychological literature that people generally do not change their behavior through these kinds of measures.

This kind of hope is a setup. A company hires a diversity consultant, and then the expectation is that everyone is now going to be more sensitive to diversity. But have we reformed our workplaces to actually be receptive and built for diverse perspectives rather than enact an assimilationist model of hiring Black, Indigenous, People of Color who are expected to conform to white-centric work environments?

Workplace cultural transformation is not simply a box to be checked or a continuing education certificate. It is an ongoing process.

The problem with this kind of hope is that there is an implicit need for a finish line, and when issues are not easily solved or are seen as too costly, hope is compromised. If we engage only to the extent that we can cross a “finish line,” we are more likely to burnout in these contexts. Hope, in this case, gives way to hopelessness and despair. Worse yet, a ‘get to the finish line’ centered motivation may indeed prevent us from even engaging in change if we do not see such change as possible.

We need hope when the outcome is unclear.

When Hope is Passive Desire

People want the world to be a better place. I think most would agree after looking at the state of the world that things could improve.

The problems faced in life and human society can seem largely unsolvable or overwhelming. When faced with these contexts, we can sometimes employ a type of hope that is merely a passive gesture. Here hope is more like a wish, a dream, or a fantasy. This type of hope requires no meaningful commitment or action.

At the individual level, we might buy a scratch ticket and, while we reveal our numbers, we hope we win — fulfilling the fantasy of having our economic struggles evaporate in a moment’s notice.

Paradoxically, passive hope can emerge as we feel hopeless about the problem. We see this kind of hope being used to cover up the anxiety of global climate change that is having real impacts on our capacity to inhabit our planet. People can feel overwhelmed and turn to a shallow passive optimism to smother out any existential dread.

Passive desire is also a comfortable resting place for those who have a great deal of privilege in the status quo. When hope is voiced in these contexts, it can smack of pity. We employ pity in settings where we don’t want to be bothered by the current circumstance because we don’t see the need to get involved. In other words, we don’t have to get involved.

We need hope that helps activate us into the struggle and energizes us into a space of connection.

When Hope is about Positive, Optimistic Emotions

The research on hope tends to get tied up with positive emotion. Now, positive emotions are essential, and the cultivation of these experiences in our lives is important. However, there can be something quite damaging to suggest that what the world needs right now is simply more positive emotions, especially if those positive emotions are the product of circumnavigating suffering.

To center ourselves into the emotional spaces of planetary destruction or intergenerational racial injustice, we need a structure that can sustain the pressure of such a place. Human emotion is ill-equipped for this journey for many reasons. First, emotions are fickle and brief. While our emotional experience is vital in our lives, we have to find a more stable compass heading than a force that moves within the prevailing winds. For me, the provocation to conjure up positive emotions is not strong enough to endure centuries of racial injustice, a century of ecological destruction, predatory economic policy, the vulnerability of the modern world against pandemics, systematic government failures, and uncertainty about the future.

Oops. Where did those positive emotions go?

Instead, we need to de-couple the pairing of hope with positive emotions in case we find ourselves engaged in meaningful work to improve the world and such emotions abandon us. Additionally, positive emotions should not be held hostage to our wish for a better future. Instead, they should be enjoyed and relished when they present themselves in our lives.

We need a hope that can sustain us through turbulence.

Radical Hope

We’ve explored the various ways in which hope may not offer us aid for the kinds of concerns we need to address in the world. Now we move onto what I think can help us in the current times.

We need a hope that is radical. The word radical refers to something far-reaching. Our hope has to be precisely that — it has to extend a great distance — in person, place, and time. Radical hope helps provide a sense of wisdom to our efforts through the power of perspective. We can get bogged down as individuals or even as activist groups by the moment-to-moment disappointments.

Radical hope helps anchor ourselves into meaningful work with a sober understanding of the present circumstances and the uphill battle we face. There is no need for optimism to be present in order to have radical hope (we will touch on this later).

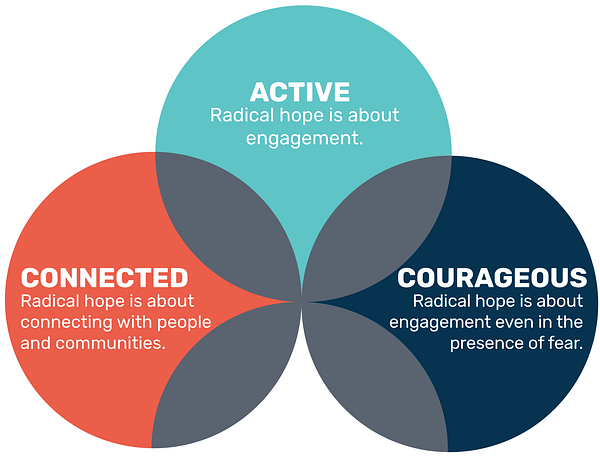

This kind of hope is different than the previously mentioned version in three distinct ways. Radical hope is active, connected, and courageous. Let’s unpack each of these elements.

Radical Hope is Active

Radical hope, first and foremost, is an activating force. It encourages us to act because there really is no alternative.

In his book, What We Think About When We Try Not to Think About Global Warming, psychologist Per Espen Stoknes notes the need for what he called active skepticism. “The active skeptic gives up the attachment to optimistic hope and simply does what seems called for.”

A radial hope cannot be too concerned with optimism. Optimism is to act as if the future is good. We don’t know that. We can’t know that. In fact, there are some real concerns in thinking like that quite frankly. So, then, how can we find hope if the future is unknown and future struggles evident?

Well, radical hope is fueled by our values, not just our goals. This is an important distinction that is made in contemporary behavioral science. Psychologists Steven Hayes, Kirk Strosahl, and Kelly Wilson note in their book Acceptance and Commitment Therapy that “values can motivate behavior even in the face of tremendous personal adversity.” Being connected to our values gives the purpose and meaning to our actions, especially during difficult times. Values, then, serve as a type of compass that helps us navigate our lives.

When we are engaged in racial justice activism, we need to be clear for ourselves and our community what values will guide us in this work. In the Black Lives Matter resource Healing in Action, they outline the need to ground oneself and to engage in purposeful visioning — which is to say to clarify why this work is so important.

Hardships are abounding for which we need a steady compass heading to navigate us through the various socio-cultural and political challenges of this work. Dominant structures and the pervasiveness of white supremacy have proven to be indelible. Therefore, we need something to revitalize us as we fight against these systems. When we act from our values we see that there are always opportunities to engage in value-driven behavior and to feel the sense of vitality that such values provide.

“Hope is not magic; hope is work. I am not certain that a new world, one of equity and justice, will emerge, but I am certain that it can emerge.” — DeRay McKesson, On the Other Side of Freedom

Radical Hope implores us to act in both big and small ways. We can often get caught up in thinking that to change major large-scale issues, we have to act in a gravitas manner that can counterweight these issues. Well, if that were the case, then these problems would not be formidable.

We all can engage in meaningful ways towards racial justice. In order to do this, we have to break out of the lure of passivity.

I’ve been involved in formal compassion cultivation training recently, and during one lesson, the meditation teacher talked about active compassion as being a practice where we look for endless opportunities, big and small, to apply compassion in the real world. To do this effectively, we need to be doing our own inner work as well as the outer work. Radical hope, also, is cultivated best when we are looking for opportunities to live out our values and practice being in the world as we would like it to be.

Radical Hope is Connected

Radial hope centers itself in connection with others. In the psychological literature, hope is predominately described as an individual subjective experience.

When hope is understood not just within our own personal experience but also in relational and community terms, it is manifested for the purpose of connection and continued resilient action in the face of adversity.

At the heart of this connection with others is the practice of gratitude for all those past and present that have contributed toward justice and ecological sustainability. It recognizes that it is through collective power that meaningful change can and does occur. Connection with others becomes the constant reminder that we are not alone and that we also have an obligation to future generations.

Radical hope, then, challenges the individualistic orientation of mainstream American culture. The issue of global climate change must be addressed by the collective efforts of the past, present, and future. It requires us to think beyond our current circumstances and connect with all those impacted (which when it comes to climate change is everybody).

Radical Hope also connects us to cultural practices that help buffer against hopelessness. Cornell West writes about this in his book Race Matters specific to the work of racial justice:

“The major enemy of black survival in America has been and is neither oppression nor exploitation but rather the nihilistic threat — that is, loss of hope and absence of meaning. For as long as hope remains and meaning preserved, the possibility of overcoming oppression stays alive. The self-fulfilling prophecy of nihilistic threat is that without hope there can be no future, that without meaning there can be no struggle.” — Cornell West, Race Matters

Dr. West goes on to share that historically it was through the cultural practices from elders to the community that helped buffer against the threat of nihilism within the Black community. This is at the heart of community resiliency.

Community resiliency is also where individuals in that community can retreat when feeling hopeless. When facing the dominant forces of our contemporary world, we need spaces and places where we can have momentary pockets of despair and doubt. Community resiliency provides opportunities for renewal and re-strengthening because there can always be someone on the front lines, but it doesn’t always have to be you!

Radical hope also draws its power from the past. The change that we want to see in the world is the work of generations rather than the effort of one protest, an election cycle, or a single piece of legislation. Think of all the struggles endured of those who came before us so that we can meet this moment.

Radical Hope is the enthusiasm of progress and solidarity in times of doubt. It connects us to something larger than ourselves for a future often beyond our vision.

Radical Hope is Courageous

Those who exemplify radial hope, both past and present, also display courage. They engage meaningful work in the presence of fear and dare to act in the face of the unknown.

Philosopher Jonathan Lear states in his book, Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation, “radical hope anticipates a good for which those who have the hope as yet lack the appropriate concepts with which to understand it.” Radial hope is a space where we embrace uncertainty. Do any of us really know what an equitable society looks like or feels like? Do any of us know for sure what a genuinely sustainable world would look like in the modern era?

How do we go somewhere we’ve never been or build something we’ve never seen? To do this work requires a kind of hope that such a space of equitable social order can exist. Radical hope encourages us to engage in meaningful work and behavior, even if we are not sure where the future will hold us.

As the maxim goes, evil is triumphant when good people do nothing. Radical hope is an orientation that directly challenges this proclivity. When we have such hope we are encouraged to engage even when we are scared, angry, or hurt. It seems vital to engage the work for this very reason.

I think it’s essential to have a kind of hope that sees us through the times when we’re not sure what we are doing or how we could be most helpful. This is much more desirable then detracting into the passive forms of hope or an intractable space of hopelessness.

In current times, I see too many people getting distracted into being the referee to social and ecological justice work rather than courageous engagement. It is easy to be an armchair critic, especially these days with social media allowing us to mark out the faults of others who dare to actually do something worthwhile. It is a massive distraction to focus on those in the stands making critical remarks on people who are actually taking risks.

The challenges of our loom large and we will certainly be imperfect when attempting to address them. In this way, hope is finding a pathway forward even if its small crack in a hard place — much like how water can cut a bolder in two. Hope encourages us to take part even if the whole outcome seems impossible and our effort limited.

Cornel West offers more of his wisdom in a chapter he wrote in the book The Impossible Will Take a Little Time: A Citizen’s Guide to Hope in a Time of Fear:

“Our courage rests on a deep democratic vision of a better world that lures us

and a blood-drenched hope that sustains us. This hope is not the same as

optimism. Optimism adopts the role of the spectator who surveys the

evidence in order to interfere that things are going to get better. Yet we know

that the evidence does not look good. The dominant tendencies of our day

are unregulated global capitalism, racial balkanization, social breakdown,

and individual depression. Hope enacts the stance of the participant who

actively struggles against the evidence in order to change the deadly tides of

wealth inequality, group xenophobia, and personal despair. Only a new wave

of vision, courage, and hope can keep us sane — and preserve the decency and

dignity requisite to revitalize our organizational energy for the work to be

done. To live is to wrestle with despair yet never to allow despair to have the

last word.”

Connected to our values and our community, we move forward step by step until we have marched truth, justice, and transformation throughout the land. And maybe it won’t be us who will be physically there when this transformation happens, but we will join the thousands of others who have come before us. The past has delivered onto us a duty to be present to this moment.

Truly this is the only way we can address complicated issues like racial justice. It encourages us to engage that which scares us, confuses us, angers us, and hurts us to encourage transformation. Through the bond of collective engagement and value-driven behavior, we stay active, connected, and courageous.

We have no other choice. The past whispers its clarion call, and the future awaits our answer.

May you find a hope that sustains you.